It is in the early-2000s that Russian cooperation with Syria was resumed and started being evolved in areas varying from economic and trade deals to military and arms agreements. Yet, for the most of the last decade, Russia took a very contradictory role in terms of its modest arms supply to Syria; with the latter expressing its vast interest in expanding the arms transfer deals. Moscow’s hesitations were primarily derived from its relations with Tel Aviv and were to some extent overcome by the late 2000s. The eruption of the Syrian crisis had changed the military relations between Russia and the Assad regime and resulted in even deeper cooperation. Thus, despite Russia’s relationship with Israel, Moscow has significantly deepened its alignment with the Assad regime. With its military intervention on behalf of Assad in 2015, Russia has manifested its engagement in Syria. This intervention served as a hallmark for Russia’s consolidation of its physical presence in the country as well as its enhancement of military/arms deals between it and the Assad regime. The Israel factor was finally overcome by Russia in late 2018 when shooting down of the Russian plane served as a trigger for Moscow to provide full-fledged arms procurement to the regime.

Restricted by Israel: Traditional Russian arms deliveries to Syria:

Russian-Assad regime military-technical cooperation includes both arms procurement (transfers) and security (military) assistance. Having inherited a long history of cooperation on the matter from the Soviet times, the relations in the military field were resumed in the mid-2000s and increased with the Syrian War, especially with the Russian intervention. Syria’s arms procurement attempts in the early and mid-2000s having been often jeopardized by Moscow’s relations with Tel Aviv. Many arms procurements were overcome by the end of the decade with Assad succeeding in the purchase of Buk-2M Ural medium-range theatre defense missiles, GM 39 Igla fire-and-forget surface-to-air missile (SAM) system, Tunguska SAMs, MiG-29SMT fighter aircraft, Pantsir S1E air-defense systems.[1] Additionally to the arms transfer deals, Russia and Syria launched a security assistance program by reviving the Tartus Naval base in 2009 and launching the Hmeymim airbase.

Moscow popping up arms deliveries into Syria

In May 2005, Russian and the regime’s finance ministers signed an agreement nearly annulling the regime’s debt owed to Russia.[2] The agreement included Russia’s consent of dropping 73% (nearly $9, 8 billion) of total debt with the remaining 27% ($3, 6 billion) of it going towards joint water, oil, gas, and other industrial projects.[3] This generosity by Moscow was based on its desire to resume its more active cooperation with the country and consequently reacquire its physical presence in the region.

This development is a strong contrast to the past where Russia hesitated to deliver arms transfers to Syria, while the latter was paying enormous efforts at the negotiations table. For instance, repeated Syrian requests to procure Russian S-300 PMU self-propelled SAM system, aircraft MIG 29 Fulcrums and MIG-31 have not been met.[4] This was based on the claim of Kremlin’s “unwillingness to upset the balance of power in the Middle East”, yet was simply a result of a strong Tel Aviv’s pressure on Moscow.[5] Additionally, Israel managed to convince Kremlin to block its sales of the Iskander-E missile batteries to Syria; the batteries were capable of sending conventional or chemical weapons payloads deep into Israel in case of a war.[6]

In 2006, Russia was committed to modernize and repair military hardware used by the Syrian army and continued to train Syrian military personnel at the senior officer level.[7] By 2006 about 10,000 Syrian officers had received training at either Soviet or Russian military academies. Furthermore, as of 2006, up to 2000 Russian military advisors were serving in the country’s military. [8]

The aforementioned Kremlin’s “minor steps” towards Damascus, in terms of arms supplies, were undertaken in 2006-2007 when Russia resumed its arms transfers to Syria by delivering the vehicle mount variant of Russian Kolomna KBM Strelets multiple launch units for use with the GM 39 Igla fire-and-forget surface-to-air missile (SAM) system and Tunguska SAMs.[9] [10]

On the verge of 2008-2009 Syria finally succeeded at purchasing several weapons from Russia that varied from modern anti-tank to anti-air missile systems. Hence, Syria upgraded its air defense capability with new Buk-2M Ural medium-range theatre defense missiles, MiG-29SMT fighter aircraft and the first batches of the Pantsir-S1 short-range self-propelled air defense system procured from Russia.[11][12]

However, since the outbreak of the Syrian War, Moscow has popped up its arms deliveries to the Assad regime vehemently. For instance, in January 2012, Rosoboronexport –Russia’s arms export monopoly- agreed to sell Syria 36 new Yak-130 combat trainer aircraft, which started being delivered in 2013.[13]

Furthermore, the arms procurement reached its culmination in the second half of 2018, when the Assad regime started receiving its long-wanted S-300 long-range surface-to-air missile systems. This brings about questions of whether Russia was no longer interested in “sustaining a balance of power in the region” as it did before and whether it’s omnipresent concern over Israel disappeared. What stood behind Russia’s disregard towards Israel this time? It was an accidental downing of a Russian military plane by the Assad regime that was trying to repel an Israeli air attack, performed by four F-16 jets, on Latakia on 18 September 2018.[14] Consequently, the Il-20 plane was downed over the Mediterranean Sea, carrying the death of 15 Russian personnel.[15] Not surprisingly, Russia held Israel directly accountable for the accident and hence provided a shaking response by upgrading the Syrian air defense system. Russia has started its S-300 anti-aircraft missiles deliveries to Syria within only two weeks after Russian reconnaissance aircraft Il-20 was shot down.[16] The Russian side declared that its delivery of the S-300 system, which is capable of intercepting air attack weapons at ranges of more than 250 km simultaneously hitting several air targets, was based on the assumption of constraining the actions of Israeli aviation.[17]

A New Era? 2017 Agreements on Tartus and Hmeymim

Before the Syrian war erupted, Russian-Syrian naval cooperation was renewed and deepened. From the Soviets, Russia inherited its sole stronghold in the Eastern Mediterranean, which remains the only Russian naval facility outside of the territory of the former Soviets; a small logistics base for its Navy in Tartus.[18] From 2009 onwards the logistical facility in Tartus is being expanded with the Russian engineers having rebuilt depot to cope with more traffic and larger ships.[19] Finally, the Syrian Crisis served as an impetus for the launch of a Russian Hmeymim air defense facility in 2015, hence reversing the course of the events in the crisis. In 2017, treaties were signed establishing Tartus and Hmeymim facilities to have a permanent Russian presence for roughly (at least) the next 50 years, of course, if the second party –the regime- is to survive ongoing mayhem.[20] The signed agreement allows Russia to expand the Tartus naval facility for 49 years and to prolong for 25-year periods on a free-of-charge basis.[21] Additionally, according to the same agreement, Russia is to enjoy a sovereign jurisdiction over the base with full immunity granted to the Russian personnel and material at the facility. Over 11 Russian ships, including nuclear vessels, are to stop at the Tartus facility on the permanent grounds.[22]

The 2017 agreement –to be precise a protocol to an amended 2015 agreement- covered the Hmeymim airbase. The Hmeymim airbase that is currently operated by Russia is located in the southeast of Latakia and shares an airfield with Bassel Al-Assad International Airport. The Hmeymim air base’s legal ground is an agreement between Russia and the Assad regime of August 2015. The base was built in mid-August 2015 for a purpose of serving as a “strategic center for Russian military intervention in the Syrian War” became operational on 30 September 2015.[23] Similarly, the agreement envisaged 49 year-long Russia’s presence on the Hmeymim base with a possible extension for the subsequent 25 year-long period.[24] Similarly, the treaty protocol set about the permanency of the Russian presence on both naval base of Tartus and aerodrome Hmeymim.[25]

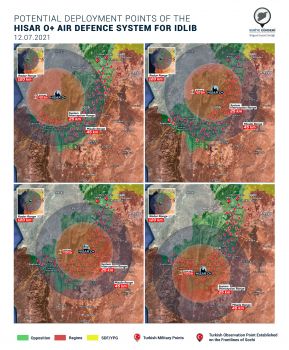

As of November 2015 onwards, the combined Russian-Syrian Air Defense force was deployed in the war zone comprises Pantsir-S1 (SS-22 Greyhound) close-in SAM/AA systems, Osa-AKM (SA-8 Gecko), S-125 Pechora-2M (SA-3 Goa) short-range (SHORAD) SAM systems, Buk-M2E (SA-17 Grizzly) medium-range SAM systems, S-200VE Vega (SA-5 Gammon), S-400 Triumph long-range SAM systems.[26] The SAM-air defense in Hmeymim airbase is composed of multiple layers. The first one of which is laid out by the S-400 and S-200 VE long-range systems. The second one is delivered by the S-300 FM Fort0M and Buk-M2E medium-range systems. It is further furnished by the Osa-AKM and S-125 Pechora-2M SHORAD systems. In the end, Pantsir-S1 is to provide coverage for the base.[27]

Conclusion

Russia’s firm stance taken in the Syrian Crisis along with its decisive military intervention in 2015 enabled the Assad regime to finally procure the arms it could not for most of the 2000s. After being restricted by Tel Aviv in terms of its arms supply to Damascus, Russia finally managed to overcome the Israel factor in the middle of the Syrian Crisis. In particular, Moscow’s respect for Tel Aviv’s security concerns minimized with the accidental shutdown of Russian Il-20 in 2018 that triggered multiply postponed delivery of S-300s to Syria.

On the other hand, the Syrian War gave a new breath to the revival of the Russian military presence in the region; the presence that is defined by its naval facility in Tartus and airbase Hmeymim. Both of the facilities being legally grounded on the aforementioned 2017 agreements foresee Russia’s ability to conserve its strongholds on the Eastern Mediterranean for at least the next 49 years. Thus, fulfill Russia’s permanent desire- access to the warm waters. Hence, an ongoing Syrian turmoil opened a window of opportunity for Russia to realize this innate interest. It is the Syrian Crisis that served as a solid ground for Russia to install its physical presence in the Middle East.

[1] “Russia defends arms sales to Syria”, UPI, 29 September, 2008, from https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2008/09/29/Russia-defends-arms-sales-to-Syria/28611222726785/?ur3=1 (Access date: retrieved 8 March, 2020)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] ‘Annual Defense Report: The Middle East and Africa”, Jane’s Defense Weekly, 14 December 2009.

[5] Andrej Kreutz, “Syria: Russia’s Best Asset in the Middle East”, IFRI, pp. 18-21

[6] Vasiliev 2018, p.387.

[7] A. Konovalov, “Russia: Defense Ministry Rules Out Supplying Offensive Weapons to Syria”, TASS, 25 January 2005.

[8] U. Klussman, “An old Base/Friendship Gets a Facelift”, Der Spiegel, 22 June 2006.

[9] “Syria Receives First Strelets SAM”, Jane’s Defense Weekly, 23 August 2006

[10] “Syria”, INSS, 19 October 2010, from http://www.inss.org.il/upload/(FILE)1287493352.pdf (Access date: 10 March, 2020)

[11] M. Hassington, “Syria receives First Batch of Pantsir Air Defenses”, Jane’s Information group-International Defense Review, 6 June 2008.

[12] “Russia defends arms sales to Syria”, UPI, 29 September, 2008, https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2008/09/29/Russia-defends-arms-sales-to-Syria/28611222726785/?ur3=1 (Access date: 8 March, 2020)

[13] “Russia sells 36 fighter jets to Syria”, The Times, 23 January 2012, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/russia-sells-36-fighter-jets-to-syria-xtxknvgtmnr (Access date: 10 March, 2020)

[14] “Russian aircrew deaths: Putin and Netanyahu defuse tension”, BBC News, 18 September, 2018, from, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-45563304 (Access date: 10 March, 2020)

[15] Ibid.

[16] “S-300 missile system: Russia upgrades Syrian air defences”, BBC News, 2 October, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-45723503 (Access date: 10 March, 2020)

[17] “Россия передаст Сирии комплексы С-300 в ответ на инцидент с Ил-20”, BBC News, 24 September, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-45624098 (Access date: 10 March, 2020)

[18] Kreuz, “”Сирия: главный российский козырь на Ближнем Востоке”, IFRI: Novemeber 2010, pp. 22-24

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Moscow cements deal with Damascus to keep 49-year presence at Syrian naval and air bases”, TASS, 20 January 2017, https://tass.com/defense/926348 (Access date: 8 March, 2020)

[21] “Moscow cements deal with Damascus to keep 49-year presence at Syrian naval and air bases”, TASS, 20 January 2017, https://tass.com/defense/926348 (Access date: 8 March 2020)

[22] “Путин внес в ГД соглашение о расширении пункта обеспечения ВМФ в Тартусе”, РИА Новости, 13 December, 2017, https://ria.ru/20171213/1510800603.html (Access date: 8 March 2020)

[23] “Договор о размещении авиагруппы РФ в САР заключен на бессрочный период”, РИА Новости, 14 January, 2016, https://ria.ru/20160114/1359734984.html (Access date: 8 March 2020)

[24] “Moscow cements deal with Damascus to keep 49-year presence at Syrian naval and air bases”, TASS, 20 January 2017, https://tass.com/defense/926348 (Access date: 8 March 2020)

[25] “Russia establishing permanent presence at its Syrian bases: RIA”, Reuters, 26 December, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-russia-bases/russia-establishing-permanent-presence-at-its-syria-bases-ria-cites-minister-idUSKBN1EK0HD (Access date: 8 March 2020)

[26] “Three layers of Russian air defense at hmeymim air base in Syria”, TASS, 26 February, 2016, https://tass.com/defense/855430 (Access date: 9 March, 2020)

[27] Ibid.