Syrian Arab Army: Limited Capacity and Fragmented Structure

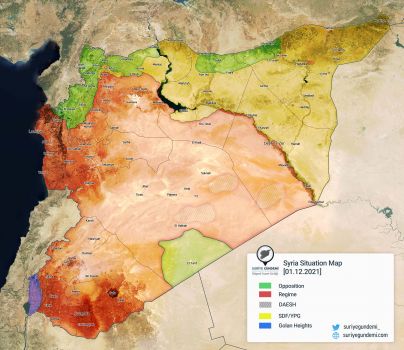

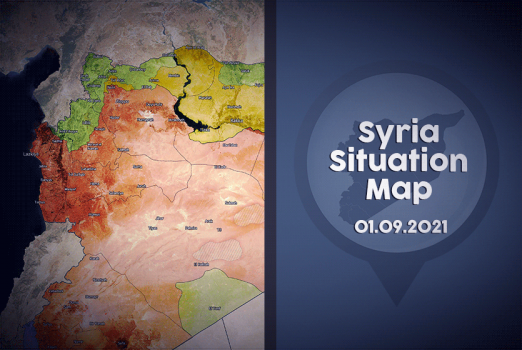

After having lost swathes of territory in the key regions of Aleppo and Damascus during the first half of the civil war, the Syrian Regime has been able to regain these areas in 2018 only after highly-destructive military incursions resulting in thousands of civilian casualties, and still only with ground and air support from Iran-backed militias and the Russian Air Force, respectively. While these successes are taken as evidence that the “regime forces” are set to be the victors of the 7-years-running Syrian Civil War, severe losses and erosion incurred by regime forces have raised legitimate doubts of its sustainability. Iranian support after 2013 in the face of rising regime losses as well as the introduction of Russian air support after the 2015 loss of Idlib has afforded the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) enough breathing room to recuperate and reclaim some of the territory it had lost. Despite this, there have been arguments that SAA is no longer a serious military force by itself, lacking the capacity to wrest control of the rest of the country in its entirety with its allies unwilling to incur the high cost of committing to this goal.

The Erosion of the Army and its Main Hurdles

Even relatively conservative Russian assessments place the military might of SAA between 70K to 80K in manpowe[1]r, down from 2011 estimates at the onset of the war at roughly 220K[2]. Aside from over 60K KIA[3], this decline owes itself to widespread desertion and defection of soldiers previously loyal to the Assad Regime. Syria and radical organizations expert Charles Lister notes that the Russians estimate the maximum number of their ally’s trained, disciplined, and effective forces to be roughly 20 thousand.[4] That SAA is deteriorating in terms of quality as well as quantity is the common view of many experts. Anton Mardasov argues that SAA no longer possesses the usual hierarchical structure normally found in regular armed forces. Instead, Mardasov speaks of the ascendency of individual elite units such as the Tiger Forces, Republican Guards, Deir al Qalamoun, and Saif al Mahdi among other forces in the army.[5] These elite units, which were established from among other elements within the army at the initiative of the regime, have become semi-autonomous in terms of firepower and funding. According to Mardasov, the latest successes attributed to the regime were in fact more reflective of the power of its allies than the effectiveness of its own military.

Security expert and retired Colonel Mikhail Khodarenok contends that not only do the Regime Forces lack the capability to successfully execute military operations on their own, but that given its current state, it would be easier to disband and rebuild SAA from scratch, rather than institute corrective reforms. Khodarenok argues that SAA has become fragmented within itself, due to its overstretch among approximately 2000 fortified checkpoints across the country.[6] Aside from these limitations, another important issue is that of the rising strength of pro-regime militias, also known as the “Shabiha”. These militia groups, which were mobilized during the early phases of civil unrest of the Syrian conflict in order to be used as a coercive force against demonstrators, became a secondary military body upon which the regime relied. Initially recruiting from individuals and groups with criminal backgrounds, the majority of these groups comprise of Alawite fighters, along with some Christian and Sunni groups.[7] As paramilitary organizations, the Shabiha lack the relative discipline and regulation of the regular military. Thus, it is likely that their rise will result in further erosion of the regular army’s hierarchical structure, handicapping its already limited military capacity. Throughout this process of attrition in the Syrian military command, it has been the Russians who have been the most active in mitigating the situation. Russia, along with Iran and Hezbollah, played a leading role in the establishment of the 5th Assault Corps. The success of this multi-sectarian force based on volunteer recruitment would position Russia as the chief actor in reshaping the Syrian security forces while at the same time consolidating Moscow’s future role in the country.[8] It has been the aforementioned deficiencies of the Regime’s security institutions that provided the circumstances necessary for such Russian action. The 5th Assault Corps has been stationed most notably on the periphery of the T4 airbase on the Homs front, as well as Hama, the Deir ez Zor countryside, and Ghouta, though it has not thus far played a decisive role on the battlefield.

SAA: Inadequate when Unaided

The ineffectiveness of SAA becomes apparent when one compares its casualties and performance in confrontations where it enjoys the support of its Russian, IRGC, Iraqi, Afghan, and Lebanese (Hezbollah) allies with those confrontations where it does not. The regime’s inability to claim similar dominance against the US-supported SDF in and around Deir ez Zor where it lacked such support, as that which it claimed in Aleppo is a clear example of such a contrast. The implication is that a SAA dependent on foreign military assistance from the Russian Air Force and Iranian-backed militias will not be able to reestablish itself as the sole authority over the US-backed SDF in the foreseeable future, as it is not seen as a decisive force either by its allies, or its adversaries. As such, it can be seen that such overtures by some analysts and politicians claiming that Turkey, “should negotiate with Assad in order to put an end to the YPG/PKK presence in Northern Syria through cooperation of the Turkish Armed Forces and SAA”, are thus unsubstantiated as they are based on the premise that the latter is an effective actor capable of functioning independent of outside assistance.

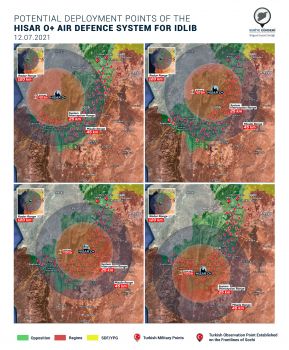

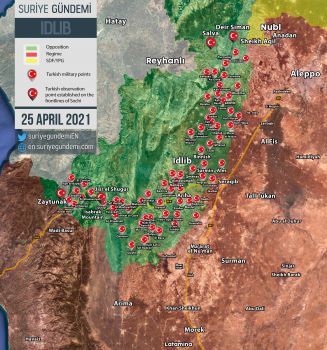

In the case of Idlib, the regime lost control of the district in 2015 due to both logistical advantages of the opposition forces in such proximity to the Turkish border, as well as limited Russian and Iranian support for the regime. At the end of the course of a few months during which the regime lost strategic points including Idlib city, Jisr ash Shugur, Ariha, and Abu Zuhur, Bashar al Assad announced for the first time that SAA was under a shortage of soldiers and that the available resources would henceforth be concentrated on the most strategic targets.[9] In the period following this statement, Russia began its campaign to directly and intensively intervene in the Syrian conflict in order to sustain the regime. Illustrative of the effect of Moscow’s intervention, the fall of Ghouta to SAA was only possible with heightened Russian air support, despite a long-running siege of the enclave.

Data on the SAA and its hitherto performance makes these basic realities clear: SAA is not capable of acting as a standalone force and in its current undisciplined state, is more akin to an army/gang hybrid than a regular military. The resultant cracks in its power and deviation from the qualities of a regular army have made it dependent on foreign assistance in the execution of successful military operations. This has brought Russia to a nearly definitive position in the formulation of Syria’s security strategy after the second half of 2015. When these circumstances are taken into consideration, it can be seen that the critical factor in the analysis of future engagements of SAA will not be its own strength, but the degree of air and command support it receives from Russia and land support from Iran in terms of IRGC presence and Iranian-backed militias.[10] The reality of which the regime’s partners are aware is that the SAA is an ineffective and costly ally. Thus, we can see that when Turkish officials pursue policy on Northern Syria, they opt to solve the issue with the actual decision-making actors, namely Russia and Iran, rather than with the Syrian Regime, which is ineffectual at this point. It is apparent that this deficiency of the SAA has played a major role in the regime’s transformation into a passive actor under the domination of both Russia and Iran.

Footnotes:

[1] Kirill Semenov, The Syrian Armed Forces Seven Years into the Conflict: From a Regular Army to Volunteer Corps, Russian Council, Mayıs 2017.

[2] Joseph Holliday, The Syrian Army: Doctrinal Order of Battle, ISW, 2013, s.5.

[3] Syria war has killed more than 350,000 in 7 years: monitor, AFP, Mart 2018.

[4] Written Testimony of Charles Lister to the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs April 27, 2017 Hearing on “Syria After the Missile Strikes: Policy Options”, Link: http://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170427/105890/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-ListerC-20170427.pdf , Access Date: 28 Mart 2018.

[5] Anton Mardasov ve Kirill Semenov, Assad’s Army and Intelligence Services: Feudalization or Structurization?, Russian Council, Mart 2018.

[6] Here’s why Assad’s army can’t win the war in Syria, CITEAM, Eylül 2016.

[7] For the thread of Tobias Schneider : https://twitter.com/tobiaschneider/status/765609696162115585 , Access Date: 1 Nisan 2018

[8] Ruslan Mamedov, The Fifth Assault Corps. Back to Order in Syria?, Russian Council, Haziran 2017.

[9] Esad: Ordumuz asker sıkıntısı çekiyor, BBC Türkçe, Temmuz 2015.

[10] Ömer Behram Özdemir, Rejim yanlısı Şii Milisler’in profilleri ve motivasyonları, Suriye Gündemi, Aralık 2017.